Although many people consider it a cosmetic issue, experts define obesity as a medical problem. Healthcare professionals recommend treating obesity to prevent various health conditions, such as heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure. This also includes specific cancers, including breast cancer.

Doctors typically diagnose obesity when an individual has a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or higher.

People come in all shapes and sizes. Obesity results from a combination of factors like genetics, physiology, environmental influences, diet, and physical activity choices. It is a prevalent and costly health issue in the United States. From 2017-2020 the obesity rate in the U.S. was 41.9%, a more than 10% increase from the previous reporting period.

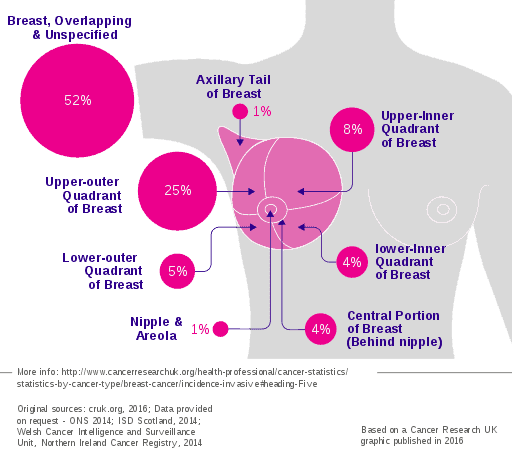

As already mentioned, obesity plays a role in many major diseases. For example, it is a known risk factor for breast cancer in postmenopausal women in the general population. However, the relationship between obesity and breast cancer risk in women with BRCA mutations is less clear. These mutations are crucial, as they have a strong link to increased risks of developing breast cancer as well as ovarian cancer. Researchers have recently sought to understand the connection between BMI and risk of breast cancer in this high-risk group to inform prevention strategies.

By doing so, this work may suggest ways in which weight health may benefit women with high-risk genetic mutations.

| This post may interest those of you with a higher polygenic risk score for breast cancer. You can read more about breast cancer genetic tests and sample reports on our blog. |

Breast cancer tissue samples and genetic studies

The study, published in Science Translational Medicine, used in vitro and mouse models to investigate the relationship between obesity markers and DNA damage in the breast tissue of women with BRCA mutations.

They started by examining breast tissue samples from 69 women without breast cancer who carried BRCA mutations and had undergone mastectomy. They found that those with a higher BMI had a greater risk of DNA damage.

They also performed several genetic studies using tissue representative of non-cancerous BRCA mutations and unaffected controls. RNA sequencing revealed that over 2000 genes were upregulated when obesity was present, while just under 2000 were downregulated. The changes were linked to DNA damage, and further investigation suggested that estrogen and other hormone pathways might drive these genetic changes and subsequent DNA damage.

Mouse models

The mouse studies sought to assess whether epithelial cell damage caused by obesity-related factors increased the presence of tumors in organisms with BRCA mutations but no clear history of cancer. They provided half the mice in the study with a high-fat diet (HFD) and half a low-fat diet (LFD). Those on an HFD had breast tissue showing similar biologic regulation as human breast tissue from women with a BMI over 25.

Like the human tissue, the researchers found that obese mice had more DNA damage and developed mammary tumors earlier than lower-weight mice when exposed to a cancer-sensitizing substance.

While they did not observe significant DNA damage in the ovarian tissue of mice with a BMI over 25, they did find increased damage in the fallopian tubes, a potential origin of ovarian cancer.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study positively associates increased BMI with DNA damage related to breast cancer risk in BRCA mutation carriers without a personal history of cancer. Those who are not obese but have obesity-related markers, like insulin resistance, may also be at a higher risk. For those with multiple factors, the effects could be cumulative on top of BRCA mutations that already contribute to DNA damage accumulation.

Since the researchers identified the estrogen pathway as a potential driver of this link, they suggest that estrogen-regulating drugs might be an effective prevention method for overweight women in this high-risk category. They also recommend investigating other obesity-related factors that could serve as targets for reducing DNA damage. Such interventions may even prolong or reduce the need for surgery.

However, the study has some limitations, such as the small sample size of 69 participants, which prevents distinguishing between BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations for personalized prevention. Additionally, the study did not account for varying estrogen levels during different stages of the menstrual cycle. Finally, the cancer model used was based on a single instance of cancer-inducing exposure, unlike real-world breast cancer which develops over time.

Citation

Bhardwaj P, Iyengar NM, Zahid H, Carter KM, Byun DJ, Choi MH, Sun Q, Savenkov O, Louka C, Liu C, Piloco P, Acosta M, Bareja R, Elemento O, Foronda M, Dow LE, Oshchepkova S, Giri DD, Pollak M, Zhou XK, Hopkins BD, Laughney AM, Frey MK, Ellenson LH, Morrow M, Spector JA, Cantley LC, Brown KA. Obesity promotes breast epithelium DNA damage in women carrying a germline mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2. Sci Transl Med. 2023 Feb 22;15(684):eade1857. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.ade1857. Epub 2023 Feb 22. PMID: 36812344.

April 21, 2023