Table of contents

Nebula Genomics DNA report for Alzheimer’s Diseases

Is Alzheimer’s disease genetic? We created a DNA report based on a study that attempted to answer this question. Below you can see a SAMPLE DNA report. To get your personalized DNA report, purchase our Whole Genome Sequencing!

To learn more about how Nebula Genomics reports genetic variants in the table above, check out the Nebula Research Library Tutorial.

What is Alzheimer’s Disease?

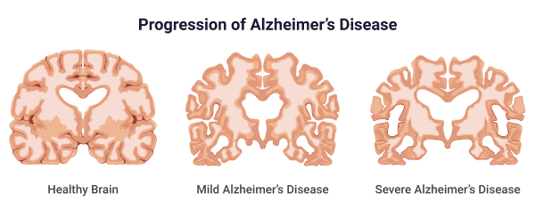

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive and irreversible condition that affects the brain, overall thinking abilities, memory, social, and behavioral skills of affected individuals. Eventually, the disease can impact a person’s ability to carry out activities in their daily life, leaving them dependent on family members or medical staff. The category of dementias include Alzheimer’s disease as a subcategory.

More than 5 million individuals in the United States are currently affected by Alzheimer’s disease. The disease can affect individuals at any time, but an individual’s risk of developing Alzheimer’s increases with age. It is the most common cause of dementia, and it has been suggested that Alzheimer’s disease may account for over 50% of all dementia cases.

Alzheimer’s is caused by the abnormal accumulation of protein pieces and beta amyloid plaque and tangles around the brain cells. This build-up leads to damage of the tissue and the eventual death of the brain cells in part of the brain. While the biology that leads to Alzheimer’s disease is mostly understood, less is known about the conditions that make an individual susceptible to the condition. Aging may be the most common and well-known risk factor associated with Alzheimer’s disease, but a number of individuals develop the condition at a younger age. While the causes of the condition are not fully understood, multiple genome wide association studies (GWAS) on Alzheimer’s disease have been performed. These studies have revealed that genetics may impact susceptibility to the condition, with multiple genes likely playing a role in the development of the disease.

Genetics of Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease is a complex disorder and can be a result of environmental factors, age, and genetic composition. It has been found that there has been a clear influence of genetics on the age of onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Based on the age at which an individual develops the disorder, it is divided into two common forms. Early-onset is typically diagnosed below 65 years old, while late-onset is the diagnosis after age 65. The late-onset Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type. Research has suggested that different genetic components may be associated with each type of Alzheimer’s disorder.

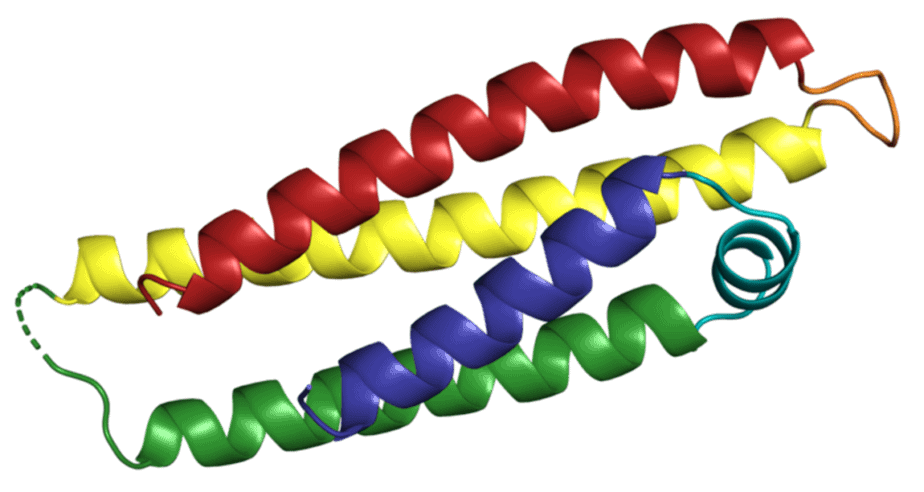

Apolipoprotein E (APOE): A gene associated with sporadic late-onset type of Alzheimer’s is the gene associated with the production of apolipoprotein E (APOE). This protein plays a significant role in mediation of neuronal protection, repair, and remodeling. The presence of particular genetic variants within the APOE gene has been associated with an increased risk of an individual developing the disease.

For example, the presence of the ε4 allele of APOE has been associated with increased build-up of the damaging proteins in the brain. As a result, the ε4 allele of APOE acts as a major risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, but does not appear sufficient to cause the disorder. On the other hand, the allele ε2 seems protective against the development of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

Amyloid precursor protein (APP): The APP gene provides instructions for the production of the amyloid precursor protein. It is found in many organs and tissues, but is particularly important in the brain and spinal cord. Researchers speculate that APP may work by helping cells connect to one another. In the brain in particular, it appears to help direct the movement of nerve cells throughout the brain’s development.

Perhaps as a result of this function during development, certain genetic mutations in the APP gene appear to impart an increased risk of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. In fact, around 10% to 15% of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease cases may be caused by the mutations within the APP gene. To date, around 50 different mutations that impart an increased risk of developing early-onset Alzheimer’s have been identified in the APP gene.

Presenilin 1 (PSEN1) and Presenilin 2 (PSEN2): Two other genes often associated with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease are both members of the same family: PSEN1 and PSEN2. The PSEN1 gene provides instructions for making the presenilin 1 protein. This protein is a part of a larger complex of multiple proteins known as the “gamma secretase” complex. This complex works to cut apart proteins into smaller fragments, which facilitates communications between cells in the body.

While the gamma secretase complex is known to cut up many different proteins, APP may be the most prominent protein that the complex processes. Due to this critical role, genetic mutations in the PSEN1 gene may abnormally process the fragmenting of APP, leading to the buildup of proteins that typifies Alzheimer’s disease. More than 150 mutations in the PSEN1 gene have been connected to early-onset Alzheimer’s. Combined, these potentially make up 70% of all cases of the disease.

Even though the exact functioning of PSEN2 is unknown, it has been suggested that its functioning is similar to PSEN1. By acting in a potentially similar role, mutations in PSEN2 may likewise be responsible for contributing to early-onset Alzheimer’s. 14 mutations of PSEN2 that may increase risk of early-onset Alzheimer’s have been identified by the researchers so far, though mutations in the PSEN2 gene are a rarer cause of the disease compared to PSEN1.

Mutations present in the genes responsible for encoding Amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin 1 (PSEN1) and presenilin 2 (PSEN2) are responsible for about many cases of the early-onset form of the disease. Therefore, family history and genetic testing may effectively predict an individual’s risk of developing the early-onset form of the disease. For late-onset Alzheimer’s, the situation remains more murky. Mutations present in the APOE gene have been associated with both increased and decreased risks of developing the late-onset form of the condition, but environmental factors likely also play a significant role.

Finally, certain mutations on genes on chromosome 21 and the extra copy of chromosome 21 that characterizes Down syndrome are uncommon genetic factors that strongly influence Alzheimer’s risk. If you want to learn more about the genetic risk, you should also look at our other reports from Deming and Kunkle.

Summary

The genetic pattern of early-onset Alzheimer’s disorder is understandable, whereas the cause of late-onset Alzheimer’s might be a bit complex to understand. Studies have suggested that the late-onset form of the condition is influenced by lifestyle and environmental impacts, but genetics also contributes to an individual’s risk. In the past few years, there has been tremendous improvement in our understanding of Alzheimer’s genetics, and additional studies in the future will continue to help define the role that our genes play in defining an individual’s risk of developing the condition.

Symptoms of Alzheimer’s

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive condition and individuals often go through various stages of memory loss and cognitive functioning. Depending on the stage of Alzheimer’s disease, people with Alzheimer’s may experience the following symptoms based on information from the National Institute of Aging.

Some aging individuals may experience mild cognitive impairment (MCI). MCI is not Alzheimer’s disease, but may increase an individual’s chances of developing Alzheimer’s disease in the future.

Early stage Alzheimer’s (mild)

A person with Alzheimer’s may function independently at this stage. They may experience some memory problems, such as misplacing objects or forgetting familiar words. While the symptoms may not be widely apparent, they may be noticed by close family and friends.

- Memory loss

- Poor judgment leading to bad decisions

- Loss of spontaneity and sense of initiative

- Taking longer to complete normal daily tasks

- Repeating questions

- Trouble handling money and paying bills

- Wandering and getting lost

- Losing things or misplacing them in odd places

- Mood and personality changes

- Increased anxiety and/or aggression

Middle stage Alzheimer’s (moderate)

This stage can last for many years. Dementia symptoms are more pronounced and the person may become confused, frustrated, or angry.

- Increased memory loss and confusion

- Inability to learn new things

- Difficulty with language and problems with reading, writing and working with numbers

- Difficulty organizing thoughts and thinking logically

- Shortened attention span

- Problems coping with new situations

- Difficulty carrying out multi-step tasks, such as getting dressed

- Problems recognizing family and friends

- Hallucinations, delusions, and paranoia

- Impulsive behavior such as undressing at inappropriate times or places or using vulgar language

- Inappropriate outbursts of anger

- Restlessness, agitation, anxiety, tearfulness, wandering—especially in the late afternoon or evening

- Repetitive statements or movement, occasional muscle twitches

Late stage Alzheimer’s disease (severe)

Individuals lose the ability to respond to their environment, carry out a conversation, and, eventually, to control movement. Communication usually becomes difficult.

- Inability to communicate

- Weight loss

- Seizures

- Skin infections

- Difficulty swallowing

- Groaning, moaning, or grunting

- Increased sleeping

- Loss of bowel and bladder control

Treatment

There is currently no cure for Alzheimer’s disease. Some medications can treat the symptoms of the disease.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved two types of Alzheimer’s medications, cholinesterase inhibitors for early to moderate stage (Aricept®, Exelon®, Razadyne®) and memantine for late stage (Namenda®), to treat the cognitive symptoms (memory loss, confusion, and problems with thinking and reasoning) of Alzheimer’s disease. While these medications can help control symptoms, neither is a cure or prevention.

For behavioral and personality, some patients may be prescribed antidepressants, anxiolytics, and antipsychotic medications.

In recent years, many novel drugs have been used in clinical trials as possible treatments for early Alzheumer’s disease. However, none have been shown clinically effective. In November 2020, the FDA failed to endorse the newest candidate, Aducanumab. The FDA has not approved a new drug for Alzheimer’s in 17 years.

If you liked this article, you should check out more posts in the Nebula Research Library.

You may be especially interested in these articles on conditions that may accompany Alzheimer’s like:

- Depression (Power and Wray)

- Schizophrenia (Psychiatric GWAS Consortium and Lam)

- Alcoholism (an addiction disorder)

- Bipolar disorder (mood disorder driven by mood swings)

- Anxiety (a mental illness marked by exaggerated fears)

May 1, 2022